From Bourbon Street to Bayous: The Call of the Wild in New Orleans

Photography by John Frim and Monica Frim

There’s no getting away from it.

If there’s one image of New Orleans that sticks out above the rest it’s Bourbon Street in the Old Quarter. Whether you’re a die-hard adventurer or an armchair wanderer, you’ve seen the beads, the balconies and the bawd—especially the bawd—if only in your mind’s eye. So it may surprise you to know that there’s more to see and do in New Orleans than amble up and down Bourbon Street—plastic two-quart cup in hand—as you drink in the N’Orlins sounds of jazz and blues along with the signature drinks of the bars en route or catch beads thrown from balconies during Mardi Gras. Even if you are not a drinker, or a partier, by the end of the day you’ll have liquefied your vocabulary with the names of Louisiana-coined libations like Hurricane, Vieux-Carré and of course the official elixir of New Orleans known as Sacerac.

New Orleans is like that. It pulls you into a sizzling, sparkling world that could, on the spur of the moment, have you thinking you’ve landed in France… or Rio…. or any of a number of exotic islands where the living is easy, the nightlife raucous, and the sips and spreads are a mix of all the flavors, smells, colors and sounds of whatever cultures happened to set foot in the newfound patria.

The Spanish were the first Europeans to explore the Mississippi and Gulf coast regions in the 1500s but the French were first to claim “La Louisiane” as a colony in 1682. Ensuing years saw the territory tossed back and forth between France and Spain until the final Louisiana Purchase in 1803 when Napoleon sold the territory to the United States. Meanwhile French and Spanish intermarried, also with people of African or Haitian descent, and became known as Creoles, differentiating themselves from the Cajuns, who were French colonists expelled in 1755 from Acadia, a colony of New France that included parts of Canada’s eastern provinces and Maine.

While the Cajuns settled in the bayous and rural parishes of Louisiana, the Creoles congregated at the sharp bend in the Mississippi River that started off as the Vieux Carré (Old Quarter), then grew to include the other neighborhoods that make up today’s New Orleans. Also known as Crescent City for its shape, or the Big Easy for its laid-back lifestyle, New Orleans is world-renowned for its French- and Spanish-inspired architecture, distinctive music, food and festivities, most notably Mardi Gras.

Locals still speak Cajun and Creole dialects and cook traditional dishes that also reflect the Irish, German and Italian bloodlines that tangled themselves into the predominantly Spanish and French communities. Specialties like beignets, a square type of doughnut, and muffuletta, a round sandwich layered with cold cuts, cheese and olive salad, are as popular as the traditional Cajun-Creole staples of boiled crawfish, jambalaya and gumbo. Visitors often use the terms Cajun and Creole interchangeably but there is a difference. At its most basic, Creole is urban cuisine, somewhat sophisticated (think French) but with a penchant for tomatoes and crawfish, while Cajun is rural, with spicy, homegrown flavorings forged in the bayous.

Most visitors to New Orleans head straight for the French Quarter for its cultural potpourri of history, food, architecture, and entertainment. Walking among historic buildings with lacy filigree cast-iron-trimmed balconies that now house restaurants, nightclubs, bars, boutiques and galleries, each with its own legend or ghost story, seems to be the best way to absorb the local vibes. Everywhere you go, the sounds of blues, ragtime, and jazz—the only home-grown type of American music—spill from the doorways or from street musicians. Outdoor vendors sell hot dogs, hot tamales and frozen yogurt alongside flowers and tourist trinkets. Artists, psychics, clowns, magicians, and human statues showcase their talents against the backdrop of St. Louis Cathedral and the Pontalba buildings that line opposite sides of Jackson Park. Converted into shops, restaurants and museums, the buildings were named after Madame de Pontalba, the dynamic Creole aristocrat who designed them in the 19th century. These buildings were the inspiration for the lacy balconies found throughout the French Quarter that now serve as launch pads for the beads and baubles thrown to pedestrians along Bourbon Street during the days leading up to Mardi Gras.

Most visitors to New Orleans head straight for the French Quarter for its cultural potpourri of history, food, architecture, and entertainment. Walking among historic buildings with lacy filigree cast-iron-trimmed balconies that now house restaurants, nightclubs, bars, boutiques and galleries, each with its own legend or ghost story, seems to be the best way to absorb the local vibes. Everywhere you go, the sounds of blues, ragtime, and jazz—the only home-grown type of American music—spill from the doorways or from street musicians. Outdoor vendors sell hot dogs, hot tamales and frozen yogurt alongside flowers and tourist trinkets. Artists, psychics, clowns, magicians, and human statues showcase their talents against the backdrop of St. Louis Cathedral and the Pontalba buildings that line opposite sides of Jackson Park. Converted into shops, restaurants and museums, the buildings were named after Madame de Pontalba, the dynamic Creole aristocrat who designed them in the 19th century. These buildings were the inspiration for the lacy balconies found throughout the French Quarter that now serve as launch pads for the beads and baubles thrown to pedestrians along Bourbon Street during the days leading up to Mardi Gras.

You can chase down historic celebrities such as Jean Lafitte in bars such as the aptly named Jean Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, which still has no electric lighting, rendering an evening by candlelight truly magical, or dine at Galatoire’s Restaurant, arguably New Orleans’ most famous, where the largely Creole menu is almost a book. Here seafood is an institution, and desserts are practically a duty. Make sure you leave room for the bread pudding or black bottom pecan pie with whiskey caramel sauce and whipped cream.

It’s easy to pummel your senses into overload in the checkerboard streets of the French Quarter, with its near-constant carousal and romp. Which is why it’s important to venture beyond Bourbon Street to the quieter neighborhoods for the unexpurgated regional details.

Faubourg Marigny, an official Historic District within walking distance east of the French Quarter, is a favorite base for many visitors. Teeming with colorful Creole cottages, funky galleries, art studios and trendy music venues this neighborhood is only slightly less boisterous than the Bourbon and Toulouse Street variety, but with plenty of charm, great eateries and quiet, shady spots such as Washington Square. Ironically, its pretentiously named Elysian Fields Avenue—after the Champs-Elysées in Paris—is anything but.

As the first thoroughfare to link the Lower Mississippi River with Lake Ponchartrain, five miles away, Elysian Fields started off with grandiose ambitions that over the years lost their zest. Tennessee Williams facetiously used Elysian Fields as the setting for his play A Streetcar Named Desire to highlight the decadence of New Orleans in the mid-20th century. Now this historical swath is undergoing an incremental process of gentrification to bring it more in line with some of the grandeur associated with its namesake in Paris, or at least up to par with Faubourg Marigny’s reputation as a premier locale for music, art and architecture.

Tennessee Williams is arguably the writer most famously associated with the literary scene of New Orleans in the mid 20th century. He lived in so many different houses in the city that entire tourist itineraries have been created around his peripatetic residences—most of them in the French Quarter. But it’s the Garden District in the west end that really draws today’s celebrities. Known for architecture more than gardens, this elite residential neighborhood abounds with Italianate and Greek Revival mansions replete with galleries, curved porticos and emblematic Doric and Corinthian columns. Walking tours lead to the homes of celebrities like author Anne Rice who once lived in a supposedly haunted mansion; Sandra Bullock, who owns a Gothic manor on Coliseum Street; or John Goodman who lives in a home once owned by Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails, who himself has other homes in New Orleans. Beyonce and Jay-Z also joined the ranks of Garden District luminaries a few years ago when they moved into a converted church. But if a church seems an eccentric purchase, it pales with that of Nicolas Cage who literally plans on staying in New Orleans forever. In 2010 the quirky actor bought two plots complete with a pyramid mausoleum in the St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, the oldest cemetery in New Orleans. He should eventually rest in good, flamboyant company. Marie Laveau the famous queen of Voodoo is buried nearby.

Between the Garden District and the French Quarter a wedge of office buildings make up the Central Business District (CBD) that tapers to a point ending at the Spanish Plaza on the Mississippi River. Surrounded by the Riverwalk Shopping Center, Harrah’s Casino and the Aquarium of the Americas, the Spanish Plaza intersects with three of New Orleans’ most popular neighborhoods: the French Quarter, CBD and the Warehouse/Arts District. A lovely waterfront walk leads from the plaza to Woldenberg Riverfront Park at the edge of the French Quarter where sculptures such as the stark white Monument to the Immigrant, the colorful Holocaust Memorial and the abstract silver Ocean Song speak to the power of public riverside art.

New Orleans is a world-class haven for artists and art collectors with galleries, boutiques and exhibitions scattered throughout the districts. But the most preeminent museums and galleries are clustered in the Warehouse/Arts District, an urbane neighborhood known for the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the Contemporary Arts Center and the National WWII Museum. Here the vibe is sophisticated and trendy but with a nod to the district’s grittier background. Coffee, cotton and grain were once stored in the warehouses, and steel, iron, copper industries and various manufacturing plants also occupied the area. Like New York City’s Soho and Meatpacking District the Warehouse District underwent a decline in the late 20th century followed by an artsy revitalization.

New Orleans is crazily two-fold, modern and traditional, in ways that are best absorbed over several days of walking through its diverse neighborhoods and sampling the culinary treats and specialties of all the cultures that added their own flourishes to the mix. But even if you have only one day, you can do a cursory cultural circuit. Take an hour or so to walk the French Quarter for its old-world charm, then amble down to the docks for a two-hour steamboat cruise along the Mississippi River. Numerous boats with similar itineraries ply the banks of the city but the Steamboat Natchez is the only local paddlewheeler that is still propelled by steam.

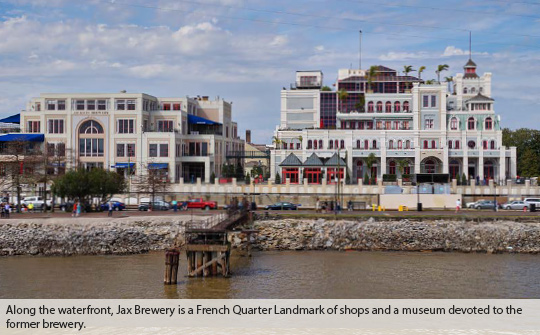

With the triple-towered St. Louis Cathedral looming over Jackson Square, the boats pull away from the docks at the Moon Walk Promenade near the Jax Brewery, a yuppie conversion of shops, galleries and restaurants, to cruise downstream past refineries, warehouses and the porticoed Malus-Beauregard House on the grounds of the Chalmette Battlefield. Now a historic park, Chalmette Battlefield was the site of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, where America’s decisive victory over the British took place, although the War of 1812 had officially ended a month earlier with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent in 1814.

The return trip upriver offers a stunning view of New Orleans that seems as incongruous as it is beautiful. One rarely associates New Orleans with skyscrapers, so it comes as somewhat of a jolt to see the lofty jagged skyline of the Central Business District loom into view. If you thought New Orleans was synonymous with Creole cottages and Victorian shotgun homes, a river cruise will let you know that New Orleans may have been a late bloomer on the skyscraper craze, but the city has finally caught on.

On a map, New Orleans looks even stranger—as the frayed toe of the battered boot that is Louisiana. Surprisingly the city is 100 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. Unlike the other states that border the gulf, Louisiana has no beach resorts and, save for a few singular patches of sand at the end points of sideroads, no beaches. There are no coastal condos, and outside of New Orleans, no swanky high-rise hotels or skyscrapers. Louisiana’s coast is definitely not clear, but tattered like a worn out rug—mouldering, fragmented, pummeled and pulverized by wind and water. The closest you’ll get to something bearing even slight semblance to a sandy beach is Holly Beach, an undeveloped coastal community of stilt houses near the Texas border. If you go, take your own food—there are no restaurants or amenities other than a few portable toilets along the coast.

According to an article on Louisiana’s disappearing coastline, written by Brett Anderson, and published in Medium.com in 2014, a part of Louisiana equivalent in size to the entire state of Delaware disintegrated into the Gulf of Mexico between 1932 and 2000. The process is ongoing with an area roughly the size of a football field slipping underwater every hour. The coast would be dissolving even faster if it weren’t for the deltaic swamps, marshes and bayous that, paradoxically, act as buffers against the frequent tropical storms and hurricanes that are largely responsible for the land hemorrhage.

A holiday here is not for the beach and party crowd, but if you need an antidote to the noise of New Orleans, there’s nothing like a sojourn among the bayous and swamplands that stretch west of New Orleans through Cajun country all the way to Texas. This is Louisiana at its widest and wildest yet it takes only 4 or 5 five hours to drive clear across the bottom of the state from the Mississippi border to Texas.

Pity to zip through though. Bald cypress trees draped in Spanish moss provide nesting grounds for pelicans, egrets and other water birds only an hour’s drive out of the city. Alligators lurk. Snakes slither. One needs to keep a watchful eye even on the boardwalks. Still there’s a special serenity in the swamps and bayous, and in the Cajun towns that you don’t find in the roistering streets of New Orleans. Set aside some time for tours of the Atchafalaya Basin with stops in historical places like New Iberia for the literary connections, Jefferson Island for its theatric associations and Lafayette for Acadian culture and folklore.

There are parts of America that are wild, primordial and magical—much loved but occasionally misunderstood. Whether that characterization is evocative of bayou country or Bourbon sprawl is simply a matter of one’s mood and nature.

- Apartments, Housing, and Real Estate

- Automotive Sales & Leasing - Cars, SUVs & Trucks

- Clothing & Apparel

- Communications & Technology

- Concierge Services

- Contracting

- Dining & Entertainment

- Education

- Event Planning Services

- Financial Services

- Health & Beauty

- Home Furnishings

- Hotels & Accommodations

- Insurance

- Medical & Dental Services

- Office Services

- Property Management

- Security Services

- Shipping & Moving Services

- Specialty Services

- Travel & Transportation