Going for Cactus, Culture and Cuisine

Photography by John Frim and Monica Frim

Phoenix

The city of Phoenix is nibbling at the desert’s edges and moving ever closer to the rust-colored mountains that encircle the Valley of the Sun. Within the city a new urbanism of locavore meals in trendy restaurants and museums co-exists with pockets of blooming prickly pears and barrel cacti. Here the most colorful desert on the planet caters to hikers, foodies and nature lovers in one fell sweep.

In Arizona’s Sonoran Desert, Phoenix doesn’t rise like its heraldic namesake but sprawls in tune with its other moniker, Valley of the Sun. In one word, it’s big. More than two thirds of Arizona’s population lives in Metropolitan Phoenix, which is not really a single city but a fusion of converging communities surrounded by mountains and, uncommonly, for a desert destination, marbled with canals, lakes, canyons, farms and green urban hubs. With more than 300 days of sunshine a year, Phoenix has been attracting sun-starved travelers for decades to attractions both indoors and out.

Natural wonders, cultural establishments and a culinary scene that’s as hip as it is healthy have turned the Valley into a spirited and spicy destination that’s hot not only in terms of its triple-digit summer temperatures, but also its food and attractions. Trendy restaurants, the likes of The Gladly, Postino’s and True Food Kitchen boast creative combinations of locally-grown organic foods that raise farm-to-table fare to artistic heights. And none more so than the award-winning Vincent on Camelback. After I sampled Chef Vincent Guerithault’s special-seven-course tasting menu that included items like frisée, arugula and prickly pear salad, mango ceviche, a ginger potato cake wrapped around a lobster claw in dill sauce, and a Grand Marnier soufflé, I didn’t need to wonder why I had gained weight.

A hike was definitely in order—especially since National Geographic rated Phoenix as one of America’s top cities for hiking.

Abundant in natural beauty, the Sonoran Desert is the most fertile and biodiverse desert in the world, crisscrossed with hiking trails and full of plants and animals that prick, poison, bite or sting. They have to be tough to survive in oven-hot temperatures on a scorched terrain that gets less than ten inches of rain a year. On the other hand, desert critters are somewhat timid—more likely to hide in cracks and crevices than pounce on human trespassers. I considered that a comforting thought as I followed our guide, who had introduced himself as Ranger B, along the well-marked trails in Usury Mountain Regional Park. The trails are easily navigable without a guide, but I appreciated having Ranger B along for his commentary on flora and fauna and practical tips on how to remove spines from cacti that attack—not that I expected to need that information. While snakes, scorpions and boar-like javelinas do their best to avoid human contact, the fuzzy cholla cactus (aka teddy bear cactus or jumping cactus) is the nastiest cactus of the desert. It breaks off at the slightest touch, hooking its razor sharp barbs painfully into flesh or latching like Velcro onto shoes and clothes. A comb will easily remove the thorns from apparel, as Ranger B demonstrated when he ever so slightly touched a cholla with his shoe. But skin contact would be a nightmare: while the spines can be removed with tweezers, their microscopic barbs can stay embedded for days.

The leather-lipped javelina, on the other hand, would rather chow down on prickly pear and agave than hikers. Coyotes, bobcats and jaguars prey on them—the javelinas, that is, not the hikers, whom they tend to avoid. Of course all bets are off if humans intervene, either by feeding wild animals (which is illegal in Arizona) or provoking them.

In every direction, bursts of greenery spring from a rust-colored gravel and rock-strewn desert floor. Palo verde trees cast lacy shadows, their brilliant chartreuse leaves and trunks standing in vivid contrast to the subtly nuanced greens of the surrounding cacti. Green and purple prickly pears, sausage-shaped chain fruit chollas, barrel cacti, and ground-hugging hedgehog cacti contrast with ocotillos (not a true cactus) reaching skywards like giant inverted squid. Here and there jojoba plants with flat, oval leaves stand like a Greek chorus along with sagebrush, mesquite and scented creosote bushes that turn acutely pungent after a rainstorm.

Looming like a sentinel, the cartoon-like saguaro cactus is the Sonoran Desert’s signature cactus because it grows nowhere else on earth. As the old man of the desert it can live more than 200 years and grow to a height of 40 feet, but takes a long time to mature, not acquiring its telltale arms until it reaches the age of 70. Just like some people, a few never grow up. For some as yet inexplicable reason they never acquire arms but stand like telephone poles all their lives.

The desert truly is a constantly evolving work of live art complemented by a plethora of luxury resorts and hotels that integrate with the landscape. Indulgent spas, gardens and private facilities are designed to calm, pamper and soothe, especially after a long day’s hike. When William Wrigley of chewing gum fame opened the Biltmore Arizona, Phoenix’s first luxury hotel, to great celebrity fanfare in 1929, he established its reputation as a haven for the rich and famous. Every American president from Herbert Hoover to George W. Bush has stayed there. The list of celebrity guests who have walked beneath its gold leaf ceiling is positively encyclopedic. Suffice to say that the grand

piano in the Wright Bar has been rendered famous by

the hands of musical luminaries like Billy Joel, Elton John and Ray Charles.

With tourism a mainstay industry, there’s no longer much talk of the once famous 5 Cs (cattle, citrus, climate, copper, and cotton) that historically drove Arizona’s economy. Today the focus is more on canyons, canals, cactus, culture and cuisine. Even the hotels incorporate new Cs into their targeted clientele. For the centrally-located Biltmore it’s celebrity. For the landmark Wigwam in the Valley’s west end, it’s casual cowboy culture but with an aura of sophistication. Its elegant casitas and suites took their cue from an early cotton ranch run by the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company. When the company officially opened the Wigwam as a guest ranch in 1929 it set the tone for expansions and refurbishments under various owners and name changes. In 2011, The Wigwam returned to its historic roots and original name in a multi-million dollar renovation project that added new facilities and reinforced that time-worn adage, what’s old is new again.

While landmark resorts with high-end facilities and high prices attract a moneyed clientele, the Valley also offers plenty of brand hotels that are more in keeping with the average leisure traveler’s budget. Though many are clustered in the heart of Phoenix, the Sheraton recently branched into Mesa, a suburb that’s turned its agricultural roots toward tourism. Situated at Wrigleyville, within walking distance of the Mesa Riverview shopping

and entertainment complex, and next to the Chicago

Club’s spring training facility, the Sheraton Mesa Hotel is also less than eight miles from the Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport.

Once an agricultural community overshadowed by the tonier suburb of Scottsdale, Mesa is coming into its own, thanks, in part, to a culinary initiative called the Fresh Foodie Trail. More than a dozen establishments invite the public in for a look-see or taste of their goods. My first stop on the Trail was at Agritopia,™ in nearby Gilbert, a farm-focused community of residential, commercial, and pedestrian-friendly spaces that has raised ecologically responsible urban farming into one of the most successful agrihoods in the movement. William Johnston, the grandson of the original owners, walked me through the property and its history. His grandparents purchased the farm in 1960 but when urban expansion encroached, the Johnston family found a way to repurpose the homestead and still preserve its history. They effectively turned the farm into a village of 452 homes (450 lots are still available as well as plans for apartments), an assisted living center and a primary school. The original homestead became a restaurant, the old quonset storage hut specialty shops, and the old tractor shed a coffee house. The central farm grows organic crops, which it markets to residents, selling the overflow at farmers’ markets and to local restaurants.

My other stop on the Fresh Foodie Trail was at Queen Creek Olive Mill, where the astounding array of olive oils and olive-based products was positively overwhelming. Co-owner Perry Rea, a master blender and olive oil sommelier, is the driving force behind this venture. He mixes, matches and infuses the oils with a variety of flavorings for what he calls “short-cut oils” because the flavorings are already in the oils so you don’t have to add them. He also beefs balsamic vinegars up with flavorings such as mosto grape reduction and peach purée. I’m there to see, taste and learn a bit about the process.

I follow Perry’s lead and pick up a small container of oil, hold it to warm it slightly, note the color, take a tiny sip, and swish it around on my tongue before swallowing, paying close attention to the feeling at the back of my throat as it goes down. I start with a pure extra virgin and progress through oils flavored with lemon, fresh basil, crushed garlic and ending with a chile olive oil that, according to Perry, gives meats, vegetables and eggs a special southern kick. It does the same for inexperienced tasters.

Then after a brief tour of the production process and a sampling of open-faced sandwiches with ingredients like baby spinach, gorgonzola cheese, and fig tapenade it was time to move on. But first a quick chat with Perry’s wife and co-owner Brenda who developed a line of spa products—soaps, lotions, butters and lip balms—from olive oil.

If there’s another C that should be added to Valley of the Sun talk, it’s creativity. Nature, food and culture find common ground as galleries, museums and restaurants work together in complementary ways. The farm-to-table food movement has curiously caught on in museums, many of which feature locally grown ingredients in their restaurants and cafeterias. Conversely, restaurants and resorts have become repositories of art and historical artifacts as they incorporate sculptures and musical presentations into their gardens and other public spaces.

It’s a symbiotic relationship that’s constantly evolving, as cactus, culture and cuisine all take inspiration from each other as well as early American Indian civilizations. The name Phoenix does, after all, stem from the mythical bird and refers to the rising of a new civilization from the ashes of the ancient Hohokam Indians, who mysteriously disappeared before the arrival of the Europeans. The miles of canals that crisscross the valley were actually the brainchild of this ancient civilization. Other native influences in agriculture are tepary beans, prickly pear cactus, and mesquite flour.

You can sample these and other locally sourced ingredients at The Heard Museum’s Courtyard Café. The indigenous food factor isn’t so unusual given the history museum’s emphasis on Native culture. Its collection includes more than 40,000 Native American artifacts as well as one of the most comprehensive displays of Hopi Kachina dolls in the world.

Traditionally, Phoenix has always played up its Southwestern roots, with themed museums that show outsiders insiders’ heirlooms and artifacts. But when The Museum of Musical Instruments (MIM) took a globetrotting leap into the world of music and acquired more than 16,000 musical instruments and artifacts—6,500 of them on display—it raised the cultural quotient of this desert oasis to unsurpassed international levels. This I had to see. I had opportunity to bang on a gong or tap out a ditty on a xylophone in the Experience Gallery, where guests can try their hand at playing the instruments, except

that my time was limited and I still had to hike through 200 countries, figuratively speaking. Reportedly, this is the largest museum of its kind in the world. In addition to seeing musical instruments from all corners of the world, you can also listen to them being played through headsets. The instruments are displayed within their cultural environments with maps of the countries of their origins, and exhibits of regional costumes, artifacts and video programs. In the Artist Gallery, you can see the instruments of luminaries such as Taylor Swift, John Lennon and Elvis Presley. This is more than a museum of music, it’s a celebration of diverse cultures and eras united by a universal language—music.

The museum is also a celebration of architecture with lines and materials that mimic the desert and mountains. Elongated windows are spaced like giant piano keys in groups of threes and twos, and subtly patterned walls allude to Arizona’s cliffs and canyons as well as the rhythms of musical composition.

It seems that music and architecture go hand in hand in the Valley of the Sun. Buildings such as those that make up the Mesa Arts Center, a performing and visual arts complex that houses four theaters, five galleries and 14 classroom studios, also hearken to the landscape with jagged angles, canted walls and colors from the desert. So devoted were the locals to building themselves a world-class art center, that they voted a tax on themselves and payed all but $5 million of the $99 million building costs themselves. Now there’s a performance worthy of laud!

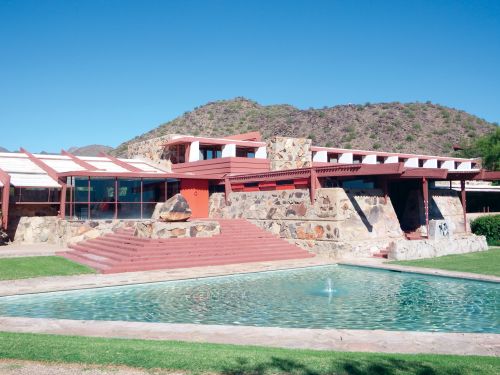

The fact that great architecture and great performances find inspiration in the landscape is borne out by West Taliesin, the winter home of, arguably, America’s greatest architect, Frank Lloyd Wright. Nestled into the McDowell range in the suburb of Scottsdale, Taliesin represents organic architecture at its finest. Here the great architect carried his version of construction that blended with the landscape to such an extreme that, for ten years, he refused to install glass in the windows because they were not natural to the desert. He eventually caved under pressure from Mrs. Wright. On a tour of the premises I got a peek at some of his quirkiest design elements, like the holes he had cut into windowpanes to accommodate vases that he refused to move even an inch from what he considered their perfect placement. Eighty per cent of the artwork in the home is original, including the piano, which visitors are encouraged to play. I almost did until someone with better musical skills beat me to the task. Instead, I sat on a replica origami chair and found it surprisingly comfortable—unlike his spindle-back chairs, which, in true FLW style, are designed to harmonize with the spaces around them, not the butts in them.

It’s said that beautiful places enkindle beautiful music. If you listen closely to the sounds of the Sonoran Desert, you just might hear a Symphony in C.

- Apartments, Housing, and Real Estate

- Automotive Sales & Leasing - Cars, SUVs & Trucks

- Clothing & Apparel

- Communications & Technology

- Concierge Services

- Contracting

- Dining & Entertainment

- Education

- Event Planning Services

- Financial Services

- Health & Beauty

- Home Furnishings

- Hotels & Accommodations

- Insurance

- Medical & Dental Services

- Office Services

- Property Management

- Security Services

- Shipping & Moving Services

- Specialty Services

- Travel & Transportation